The Starry Night, 271 :: home :: |

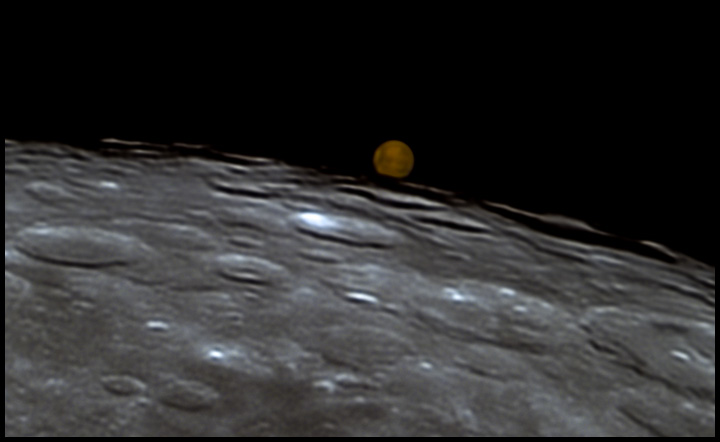

Marsrise.

56 years and 13 days later, on January 13, 2025, the Moon and Mars aligned as seen from the northern hemisphere of planet Earth. Here's my best effort to capture that event and offer an echo of "Earthrise."

The Moon is presented as a 4-panel mosaic, each comprised of the best 400 of 4,000 frames. USAF General William Anders, retired, 1933-2024, was "that old guy who hangs around the airport" flying whenever he had good weather and a spare minute and assisting amateur aviators at Skagit Regional Airport with this and that. I doubt that all the people who encountered him in the hangers beside the Heritage Flight Museum knew who he was. Bill Anders was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 8, an Apollo mission without a lunar module. It's fun to imagine conversations slipping or skidding into "that time back in '68 when I flew to the Moon."

By NASA/Bill Anders, Earthrise

Tech-talk.2025/01/15: For them what care... I wanted more of the Moon than the tiny sensor in my one-shot-color camera, a ZWO ASI462MC could get. The solution to that is easy and routine: shoot a mosaic. Use FireCapture to collect some overlapping moonshots, use the same settings for each, process them identically (AutoStakkart!4), and stitch them together (Photoshop) into a wider view. Courtesy of Bill Gray's Guide 9.1 software, I knew Mars would reappear at 22:19:52 EST, give or take a few seconds depending on the exact geometry of the lunar limb, and I knew where along the lunar limb it would reappear. The rehearsal images from the night before were OK. They gave me reasonable settings for gain and exposure and were passably sharp. Just before the real event, I pointed the telescope at Pollux and focused with a Bahtinov mask. Each subframe of the lunar mosaic used the best 400 frames of 4,000-frame 12-bit videos. Each video took about 85 seconds to capture. I finished with the frame that would capture the reappearance of Mars. I got there early, but started immediately just in case Mars popped up before I expected it. That video ran to something over 14,000 frames because Bill Gray writes good software, and Mars was right on time. (For consistency, I selected a 4,000-frame clip with which to complete the mosaic). From that long video, I could also isolate the several hundred frames that included Mars's emergence from the unseen limb of the Moon. The lunar limb was invisible because the occultation ended a few hours after the Moon was full. Mars reappeared along the narrow, unlit western edge of the Moon where the Sun had just set. By aligning those frames on the Moon but not on Mars, Mars formed a short streak rising behind the rim of the crater Sklodowska (Marie Curie's family name; her husband Pierre has a smaller crater nearby). That allowed me to capture the horizon behind which Mars would rise. [Keep reading; this approach did not work as well as the alternative described below.] As soon as Mars cleared the Moon far enough for me to isolate it in a tiny region of interest on the camera's sensor, I took a long video (a little over 25,000 frames at about 200 fps). For this clip, I increased the camera's gain to allow 1 millisecond exposures. That allowed me to use AutoStakkart!4 to isolate the best 2% of the data and produce a reasonably sharp image of Mars free of electronic noise with much-mitigated atmospheric turbulence. Despite Mars being very high in the sky, there seemed to be a noticeable amount of atmospheric dispersion: something misaligned the blue, green, and red images by about 2 arc seconds. I moved the channels around in Photoshop to minimize that. The streak approach left the shape of the dark lunar horizon well defined but also involved a good bit of ambiguity about the exact position of Mars's reappearance relative to nearby lunar features. I tried an alternative: I selected a one-second interval from the video that included Mars's reapparance and used AutoStakkart!4 to align the entire image, as usual. Then I cropped the portion containing Mars and a small set of lunar features, enough to register the image with the higher resolution moonscape mosaic.

Given the unsteady air, that brief clip could not provide as clear an image of fine details on the Moon or Mars, but it came surprisingly close. It sufficed both to define the relatively gross silhouette of the lunar horizon against the Martian deserts and permit the image to be registered with arc-second accuracy in the widefield mosaic. With that done, I masked the higher resolution image of Mars with the low-resolution Martian image, leaving only the higher resolution image of Mars above the horizon as defined in the lower resolution image. (All this might be more straightforward, or more frightening, if you could see me wave my hands around. Or maybe I could use index cards to represent the various layers involved.) Nothin' to it. Here's 1080p video on Vimeo. I used a 10-inch RC at prime focus and a ZWO ASI462MC camera behind a UV/IR filter (full frame, 12-bit, bin 1, gain 100, 1.9ms exposure, 48fps). Camera control and data capture: FireCapture 2.7.14; PIPP for SER to AVI; AVI to MP4 conversion and image stabilization, Adobe Premiere Elements 15. The still frame was produced using AutoStakkert!4 for stacking, ImPPG for deconvolution, and Photoshop for presentation.

:: top :: |

© 2025, David Cortner