The Starry Night, 235 :: home :: |

William Denning's Galaxy

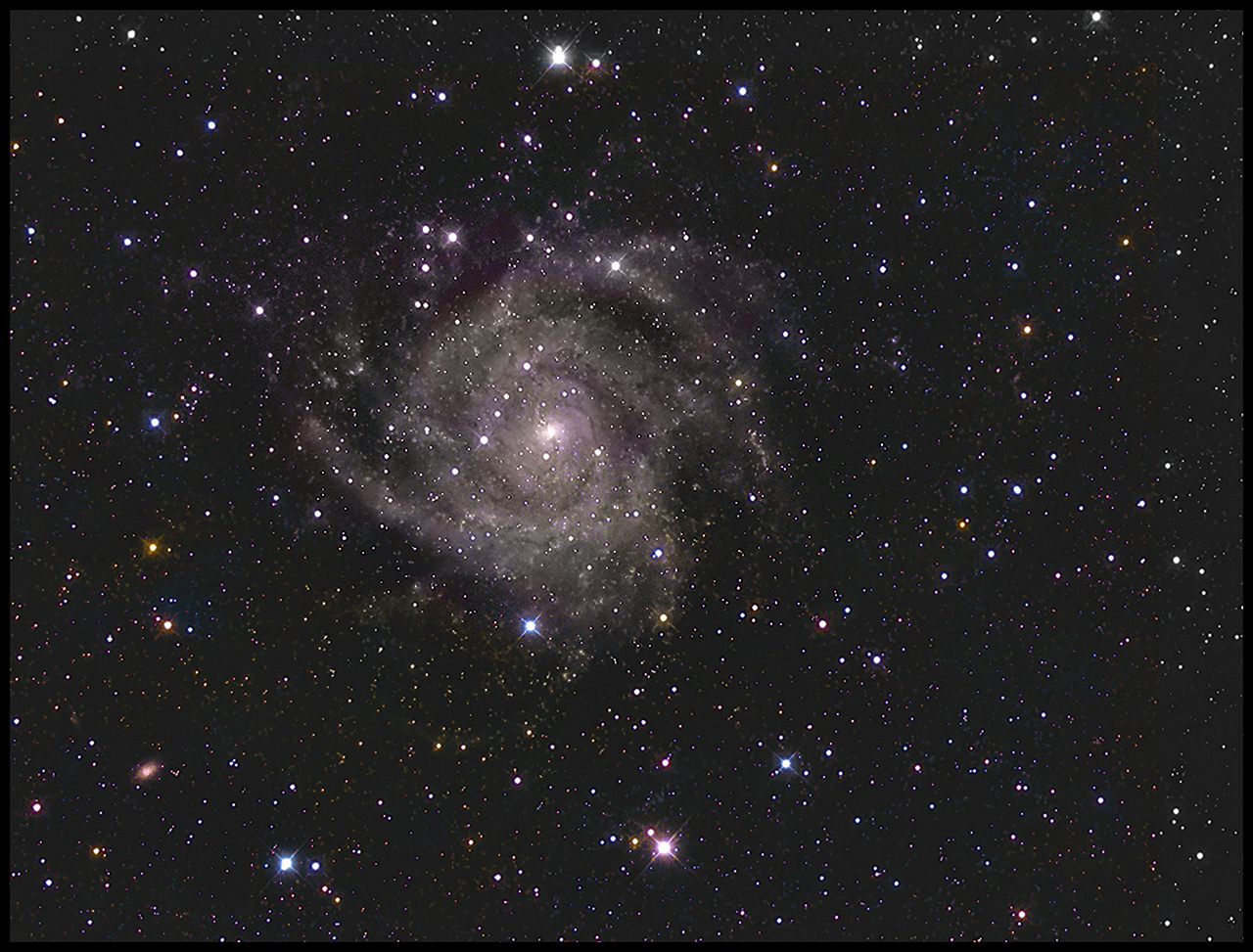

11/17/2022. Late in the evening, I revisitted IC 342, which I shot years ago. Last week, I played with some images stolen/borrowed/sampled from Astrobin which suggested it would be a great subject for star removal. Of course! It's a galaxy hidden by stars. Here's last night's photo, first with stars, then with reduced stars: The telecope- and camera-control computer shut down earlier than I thought I'd set it to do. So these are a little "thin." Two nights later, following a late-night frontal passage, I collected an additional 3 hours of data evenly split between red and blue filters. I synthesized the green channel and added them all to the luminance data above:

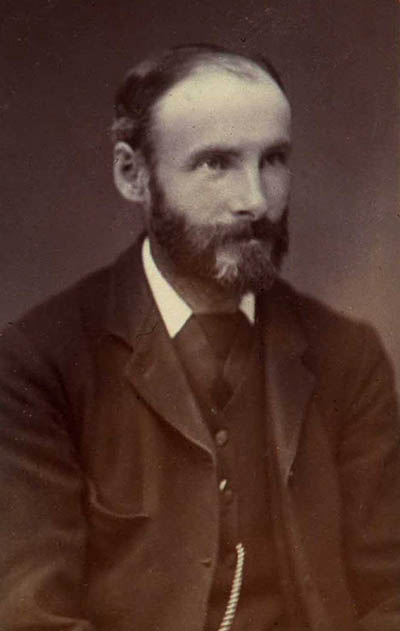

Here's the fun thing: IC 342 is one of the biggest, nearest, and brightest galaxies in our skies. It's between 7 and 10 million light-years away (which? why is that hard to know? Another source says "10.8 million light-years" so just pick one), and it's a decent fraction of full-moon sized. But it's an IC object -- it has no Messier number (because Charles didn't see it) and no NGC designation (because William, Caroline and John Herschel didn't spot it). It's in the Index Catalog where John Dreyer put it in 1895 based on a letter ("before 1894") from amateur astronomer (and professional accountant) William Frederick Denning. Dreyer summarized Denning's description for the Index Catalog ("pretty bright, very small") and called attention to the 12th magnitude star close by. Denning had also published his observation under the news and notes section of Vol 12, Astronomy and Astro-Physics, for 1893, reproduced below. W. F. Denning was the Leslie Peltier of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Leslie was the Leslie of the mid 20th century). He observed from his home (Bex Villa, Morley Square, Bishopston, Bristol). His book, Telescopic Work for Starlight Evenings (1891) is at times fun and discursive (and at others long and tedious, as seems to be required for astronomy texts of that era). Where Leslie was Mr. Variable Stars, W. F. Denning attended to something closer to home.

William Denning specialized in meteors. He catalogued fireballs, showers, and storms, and his observations and analyses of their intensities, speed, and radiants helped define the characteristics of several major and minor displays. Denning nailed down the fact that the Perseid radiant moved from night to night. He championed the idea of "stationary radiants" which remained fixed in the sky for weeks on end. That phenomenon didn't make sense to him or to anyone else and many did not credit its reality, but William Denning, accountant, believed his numbers and his data and stood by what they suggested. In 1870, when 22, Denning purchased a 10-inch reflector [Monthly Notices RAS, 1898, v58, p242; Telescopic Work, fig 19] which he used for the rest of his observing career to hunt comets (he discovered four, five if you include one found by Edward Emerson Barnard the night before, March 30, 1891) and to study the planets. He measured the rotation of Mars (24h 37m 22.34s sidereal said he, which agrees to the second with the 21st Century value, [Nature, May 15, 1884]) and was especially adept at observing markings in Jupiter's atmosphere. He was a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, has an asteroid named after him as well as a crater on the Moon and another on Mars. In his capacity as the de facto expert on falling stars, he even rated a mention, by name, in H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds. Mr. Chambers reported to the December 1897 meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society that he "happened to have a few spare hours at Bristol some time ago, and I called upon Mr. Denning and had a very profitable interview with him. I came away with the impression that Mr. Denning, although a great genius in the matter of meteors, is not one of those self-advertising geniuses of whom we hear too much in the present day." [Dec 1897, Proceedings at Meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society, p 437] The Royal Astronomical Society was keen to have him attend their meetings, but they were routinely disappointed. "I should like to put on record an expression of regret, when we are talking about meteors, that we never have the pleasure of seeing amongst us our first British meteor observer, Mr. Denning," said Professor H. H. Turner in November 1897 while the RAS anticipated a Leonid shower. "It would give us very great pleasure if we could have Mr. Denning amongst us, even for once, to hear what he has to say about the approaching display." [Meeting of the RAS, Friday, November 12, 1897] Three months later, when the Society awarded Denning their Gold Medal for 1898, he was not amongst them for that, either. The RAS published a 12-page single-spaced hagiography to mark the occasion.

Dreyer's Index Catalog describes entry #342 as "pretty bright, very small," and notes a faint star close by, conspicuous by its proximity. That describes only the innermost central condensation of Denning's galaxy. On August 19, 1892, Denning discovered the new nebula while comet hunting. His "comet eyepiece" yielded a wide field of view at only 40x and allowed Denning to sweep wide swaths of the sky. When something interesting turned up, Denning changed to an eyepiece yielding 145x to allow closer examination and measurement. Supposing that his eyepieces were typical of the day, then his field of view at higher magnification was only about 17 minutes of arc. What Denning actually saw looked more like this than like the photos above:

As far as its discoverer knew, IC 342 was just one among 21 faint nebulae he discovered while comet hunting. Only in 1934 did Edwin Hubble and Milton Humason recognize that it was actually the core of a spiral galaxy. The following May, in a survey of photographic evidence of the newly understood object, Harlow Shapley and Carl Seyfert wrote in Harvard College Obsveratory Bulletin #899 that IC 342 was, "the almost stellar nucleus of an exceptionally large faint-armed spiral nebula. In angular diameter the spiral is, in fact, one of the largest in the sky..." and attributed the faintness of the spiral arms to "space absorption existing in [its] low galactic latitude." This was pretty much the final word on the nature of the object; subsequent work has amounted to filling in more details: it's a starburst galaxy, one in which stars are forming at a rapid rate in many locations, and as such, it's rich in H-II regions. The even-more-obscured galaxies Maffei-1 and -2 recognized / discovered in 1968 are companions of IC 342, which is not, contra Shapley, a part of the local group along with the Milky Way, M31, and M33. As late as 2020, the distance of the members of the Maffei / IC 342 assembly remain somewhat inconsistent when measured by various metrics.

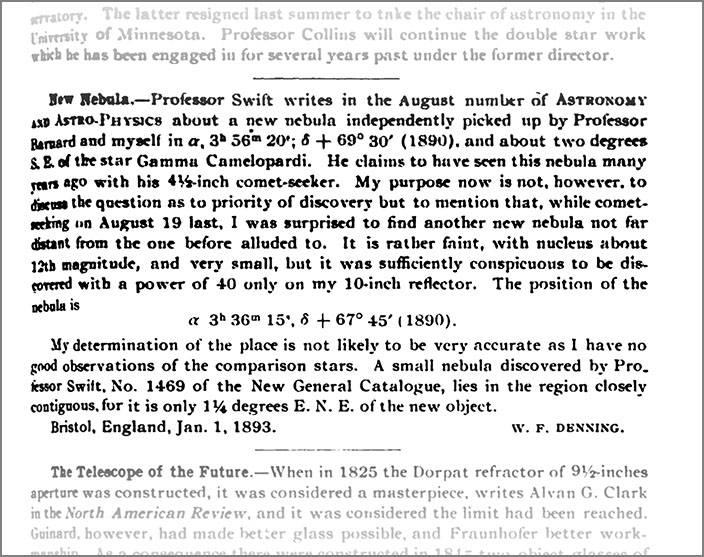

An alternate history. Other sources, most notably Edward Emerson Barnard, say that IC 342 was discovered by the American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard in 1890. Barnard and Denning vied for priority on comet discoveries in the early 1890's. In parts of the Index Catalog, their names alternate from one diffuse bit of overlooked nothing to the next. When Barnard suggested that some nebulae were variable, thus explaining how they could be overlooked by some observers but readily seen by others, Denning wrote a response which was totally British in its politieness and eviscerating in its Britishness. On August 11, 1892, he surveyed a few other cases where variability of nebulae had been cited to explain when, how, and by whom a nebula was first seen, and then he got down to business. "Mr. Barnard claims to have discovered [a particular] nebula in Camelopardalus in August 1889 whereas I did not pick it up until November 1890," wrote Denning of IC 356. "While admitting this claim I would venture to remark that any one who makes a discovery ought to be prompt in announcing it as a delay by several years is very likely to cause misconception and unnecessary trouble to others. I think that in ordinary cases prirority of announcement ought to be accepted as priority of discovery. This seems the most business-like way of dealing with such questions. Of course when an astronomer of Mr. Barnard's reputation claims to have anticipated a published discovery we can accept his word for it but in all such cases the immediate notification of discoveries is most desirable as it affords a guide to later observers who may possibly meet with the same objects and thus be prevented from taking useless trouble." When John Dreyer drew up the Index Catalog, Barnard and Denning were listed as co-discoverers of IC 356. E. E. Barnard was not the only other claimant. Professor Lewis Swift, a hardware mechant turned professional astronomer, was from a generation of observers just prior to Barnard's and Denning's, and he also asserted priority for IC 356. Swift discovered well over a thousand new nebulae. He and Denning were frequent correspondents. On January 1, 1893, six months after his letter about the need for prompt announcements, Denning wrote to "Astronomy and Astro-physics" to make known Swift's claim. Then he went him one better with a new discovery of his own:

"News and Notes" section of Astronomy and Astro-Physics

Dreyer soon listed this new, "rather faint" nebula with a 12th magnitude nucleus as IC 342. Modern day astrophotographer Martin Germano wrote that Barnard claimed to have "discovered IC 342 on 11 Aug 1890 with the 12-inch refractor at Lick Observatory. He noted 'with 500x it is quite a bright object, 1/2 minute' dia and quite [?], mbM, not cometary." Martin says that Barnard neither published this observation nor communicated it to Dreyer who was then compiling the Index Catalog (maybe it's in unpublished notebooks at Lick?). Alas, despite the widespread mention of Barnard's name in connection with IC 342, I have not been able to find a primary source or any other specifics about his observation.

:: top ::

|

||||

© 2022, David Cortner